Mebendazole (Fenbendazole) Proposed to Replace Current "Gold-Standard" in Brain Tumor Treatment

Gold-Standard vincristine is neither as effective or safe as mebendazole

This article will present and review one scientific paper that lays out the case made by these researchers for the use of mebendazole (used interchangeably with fenbendazole)1 in the treatment of brain tumors. First, it covers a series of peer-reviewed experiments in the prestigious journal Molecular Medicine proving that mebendazole is a more effective and safer alternative in the treatment of brain tumors than vincristine, the current “standard of care” chemotherapy. Regarding terminology, brain tumors encompass a wide variety of conditions but approximately 80% of brain tumors are classified as “diffuse gliomas.” Second, the scientists explicitly call upon the powers that be for the immediate replacement of the current chemotherapy for brain tumors using side-effect laden vincristine in favor of safe and effective mebendazole. Third, these data showing the clear superiority of mebendazole in treating brain tumors and the pleas to replace vincristine with mebendazole have been routinely ignored.

A 2017 study directly compared the drug vincristine, the “gold-standard” treatment for brain tumors, with mebendazole, in a series of in vitro (petrie dish) experiments, and concluded, based on efficacy and safety results, that mebendazole be strongly considered to replace vincristine as the standard of care treatment (DeWitt, et al., 2017).

When scientists in the oncology field sing the praises of an alternative treatment that is safe, effective, inexpensive and off-patent like mebendazole it is worth reproducing those words exactly. From the paper we quote “Anthelmintic drugs have gained attention in the last two decades as potential anticancer agents due to their interactivity with microtubules (Guerini et al., 2019; Son et al., 2020; Armando et al., 2020; Nath et al., 2020). In particular, a wide range of cancer cells and animal models showed the possible effect of mebendazole in inhibiting tumor cell growth through its ability to inhibit tubulin polymerization, leading to a lethal effect in rapidly dividing cells. The potential effect of mebendazole in inhibiting cancer cell growth has been described in thyroid (Williamson et al., 2020), gastrointestinal (Mansoori et al., 2021), breast (Choi et al., 2021), prostate (Rushworth et al., 2020), pancreatic (Williamson et al., 2021), ovarian (Elayapillai et al., 2021), colorectal (Hegazy et al., 2022), melanoma (Simbulan-Rosenthal et al., 2017), head and neck (Zhang et al., 2017), leukemia (Freisleben et al., 2021), and bile duct cancer (Sawanyawisuth et al., 2014). In addition, mebendazole is relatively non-toxic for normal cells, whereas it increases its specific sensitivity in cancer cells. Regarding brain cancer, several studies demonstrated the antitumor properties of mebendazole” (Bai et al., 2021 for example).

Meco et al., (2023) continue “Many research groups have investigated mebendazole as a tubulin polymerization inhibitor and strongly recommend its clinical use as a replacement for vincristine for treating brain tumors (DeWitt et al, 2017). In addition, many studies demonstrated its capability in reducing angiogenesis, arresting the cell cycle, and targeting several key oncogenic signal transduction pathways. Therefore, mebendazole’s ability to hit multiple targets can improve the efficacy of anticancer therapy and help overcome acquired resistance to conventional chemotherapy.”

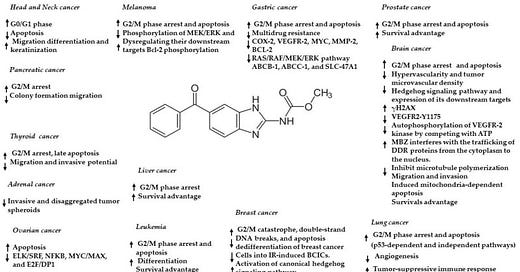

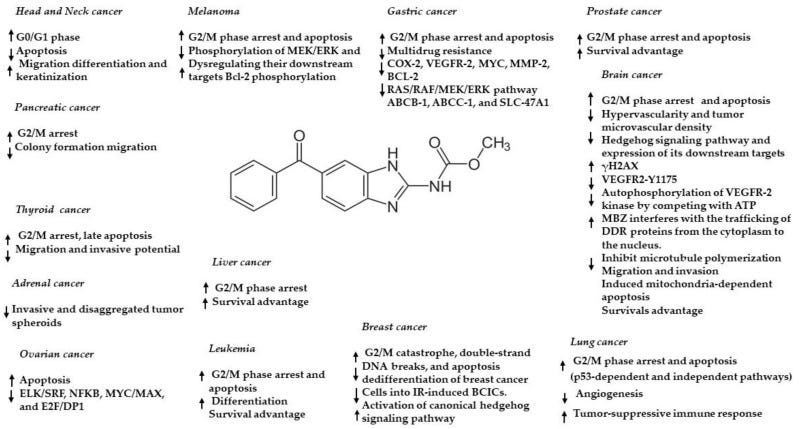

So, there are a couple of compelling questions raised in the previous two paragraphs. One question surrounds the issues with current vincristine treatment for brain tumors and why alternatives are necessary. Another issue is the overwhelming, yet apparently circumstantial evidence indicating mebendazole’s use as an effective cancer treatment. Finally, there is some uncertainty regarding the exact mechanism through which mebendazole exerts its cancer cell killing effect. Is it blood vessel growth inhibition (starving the cells of nutrients), cell cycle disruption (mitotic arrest, apoptosis or some other disruption pertaining to cancer cell division), microtubule growth (polymerization) or one or more of the dozens of other identified mechanisms through which mebendazole can kill cancer? (see Figure below).

Anticancer effects and mechanisms of action of mebendazole in different cancers. Arrow up = upregulation/activation, arrow down = downregulation/inhibition. From Meco et al., 2023.

Regarding the current treatment for brain tumors, DeWitt et al., (2017) question how vincristine ever became the “gold standard” in the treatment of brain tumors in the first place. Vincristine doesn’t cross the blood brain barrier effectively (Boyle, et al., 2004), and in concentrations necessary to cause any measurable levels in the brain, a host of debilitating side effects including painful neuropathy appear (Gidding, et al., 1999).

Next, DeWitt, et al. (2017) observed the effects of mebendazole on experimental glioblastoma cells implanted into a mouse brain, to produce brain tumors, and compared these effects with those of vincristine on overall survival of the animals. Basically, vincristine did not prolong the survival of the mice compared to a control group given brain tumors but no therapeutic treatment. In contrast, mebendazole-treated mice with experimental brain tumors lived almost 100% longer than untreated controls with brain tumors. Note: this experiment was not designed to cure the mice of the implanted brain tumor (which we know from other reports does happen see Johns Hopkins Medicine), and this Substack (Case Report: Diffuse Midline Glioma, age 27, male) but only to measure how vincristine and mebendazole affected the growth of the tumor.

With respect to the mechanism through which mebendazole exerts its specific cancer cell killing effects, a series of clever experiments (available in detail in DeWitt, et al., 2017 for those interested) definitively determined that microtubule depolymerization (breakdown) accounted for the anti-cancer effect. The dissolving of the microtubules occurred in cancer cells only, not normal healthy cells.

The author’s words are enlightening “The extensive use of vincristine in brain tumor therapy (van den Bent et al., 2013; Cairncross et al., 2013; Buckner et al., 2016) dates back to a phase II study using a combination of procarbazine, CCNU (aka lomustine) and vincristine to treat a wide range of brain tumors (Gutin et al., 1975). The introduction of this combination was based on the therapeutic activity of procarbazine in an intracerebral rat leukemia model (Grunberg 1970) and that of CCNU in orthotopic models of glioma and ependymoblastoma (Shapiro et al., 1971). Including vincristine in this regimen was based on limited clinical experience in a small number of patients (Lassman et al., 1965; Smart et al., 1968).”

So here we have a drug, vincristine, that has been used for decades that apparently was incorporated into the “standard of care” for gliomas that had very little data to support its initial use and, as DeWitt et al., (2017) conclusively demonstrated, doesn’t work on gliomas! How many were given false hope being treated with vincristine only to succumb because the treatment was ineffective from the start. The irony embedded in the term “Gold Standard” when used in reference to many pharmacological treatments, including vincristine, doesn’t apply to the safety or efficacy of the drug as assumed, but rather to the riches to be gained from those producing and prescribing that drug.

We mentioned that the calls to replace vincristine with mebendazole by DeWitt et al., in 2017 were ignored. That assertion is made because a toned down, perhaps more politically correct (read Big Pharma fearing) follow-up to that paper was published in 2023 by Meco et al. Emerging Perspectives on the Antiparasitic Mebendazole as a Repurposed Drug for the Treatment of Brain Cancers which makes many of the same arguments 6 years later.

To tie this all up, recall that one of the Case Reports in this Substack, a 27 yr old man eradicated his diffuse midline glioma brain tumor with 888 mg fenbendazole per day. This Case Report is extremely encouraging because it is a logical extension of the in vitro and pre-clinical data cited above that strongly indicate that fenbendazole is safe and effective in treating human brain tumors. This Case Report detailing successful self-treatment with fenbendazole, with no adverse side effects, is consistent with the foundational data.

Where to get fenbendazole

In our experience and the experiences of those that write in, it appears that the three readily available brands of fenbendazole (Panacur-C, FenBen Labs, Happy Healing Labs) are equally effective. Panacur-C can be obtained locally in pet stores, while they all can be obtained from Amazon.

If you would like to report your experiences with fenbendazole you can do so privately by email fenbendazole77@gmail.com or more publically in the Comments section in any of the articles. Also, if you know of people who’ve tried fenbendazole, and it didn’t work, we’d be especially interested in hearing from you now. Understanding the conditions and factors that enhance or impede the success of fenbendazole in treating cancer are valuable. As an example, we recently learned that pairing fenbendazole with oleic acid, olive oil has high oleic acid content, greatly enhances the bioavailability of fenbendazole (Liu et al., 2012). As a practical application of this information taking fenbendazole with a tablespoon of olive oil may result in better outcomes.

References

Armando R.G., Mengual Gómez D.L., Gomez D.E. New drugs are not enough drug repositioning in oncology: An update. Int. J. Oncol. 2020;56:651–684. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.4966. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Bai R.Y., Staedtke V., Wanjiku T., Rudek M.A., Joshi A., Gallia G.L., Riggins G.J. Brain Penetration and Efficacy of Different Mebendazole Polymorphs in a Mouse Brain Tumor Model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:3462–3470. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2681. [PMC free article]

Boyle FM, Eller SL, Grossman SA (2004) Penetration of intra-arterially administered vincristine in experimental brain tumor. Neuro. Oncol. 6:300–05.

Buckner JC et al. (2016) Radiation plus Procarbazine, CCNU, and Vincristine in Low-Grade Glioma. N. Engl. J. Med. 374:1344–55. [Article]

Cairncross G et al. (2013) Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term results of RTOG 9402. J. Clin. Oncol. 31:337–43. [Article]

Choi H.S., Ko Y.S., Jin H., Kang K.M., Ha I.B., Jeong H., Song H.N., Kim H.J., Jeong B.K. Anticancer Effect of Benzimidazole Derivatives, Especially Mebendazole, on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) and Radiotherapy-Resistant TNBC In Vivo and In Vitro. Molecules. 2021;24:5118. doi: 10.3390/molecules26175118. [PMC free article]

De Witt M., Gamble A., Hanson D., Markowitz D., Powell C., Al Dimassi S., Atlas M., Boockvar J., Ruggieri R., Symons M. Repurposing mebendazole as a replacement for vincristine for the treatment of brain tumors. Mol. Med. 2017;23:50–56. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2017.00011. [PMC free article]

Elayapillai S., Ramraj S., Benbrook D.M., Bieniasz M., Wang L., Pathuri G., Isingizwe Z.R., Kennedy A.L., Zhao Y.D., Lightfoot S., et al. Potential and mechanism of Mebendazole for treatment and maintenance of ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021;160:302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.10.010. [PMC free article]

Freisleben F., Modemann F., Muschhammer J., Stamm H., Brauneck F., Krispien A., Bokemeyer C., Kirschner K.N., Wellbrock J., Fiedler W. Mebendazole Mediates Proteasomal Degradation of GLI Transcription Factors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:10670. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910670. [PMC free article]

Gidding CE, Kellie SJ, Kamps WA, de Graaf SS (1999) Vincristine revisited. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 29:267–87.

Grunberg E (1970) Experimental tumor inhibitory activity of procarbazine. In: Carter SK, ed. Proceedings of the Chemotherapy Conference on Procarbazine. Bethesda, MD: US Govt. Printing Office, pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar ]

Guerini A.E., Triggiani L., Maddalo M., Bonù M.L., Frassine F., Baiguini A., Alghisi A., Tomasini D., Borghetti P., Pasinetti N., et al. Mebendazole as a candidate for drug repurposing in oncology: An extensive review of current literature. Cancers. 2019;11:1284. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091284. [PMC free article]

Gutin PH et al. (1975) Phase II study of procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine combination chemotherapy in the treatment of malignant brain tumors. Cancer. 35:1398–404. [Article]

Johns Hopkins Medicine (2014). https://clinicalconnection.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/surprise-finding-yields-a-possible-tumor-fighting-drug

Hegazy S.K., El-Azab G.A., Zakaria F., Mostafa M.F., El-Ghoneimy R.A. Mebendazole; from an antiparasitic drug to a promising candidate for drug repurposing in colorectal cancer. Life Sci. 2022;15:120536. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120536. [PubMed]

Lassman LP, Pearce GW, Gang J (1965) Sensitivity of intracranial gliomas to vincristine sulphate. Lancet. 1:296–98. Article

Liu, C. S., Zhang, H. B., Jiang, B., Yao, J. M., Tao, Y., Xue, J., & Wen, A. D. (2012). Enhanced bioavailability and cysticidal effect of three mebendazole-oil preparations in mice infected with secondary cysts of Echinococcus granulosus. Parasitology research, 111(3), 1205–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-012-2954-2

Mansoori S., Fryknäs M., Alvfors C., Loskog A., Larsson R., Nygren P. A phase 2a clinical study on the safety and efficacy of individualized dosed Mebendazole in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021;26:8981. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88433-y. [PMC free article]

Meco, D., Attinà, G., Mastrangelo, S., Navarra, P., & Ruggiero, A. (2023). Emerging Perspectives on the Antiparasitic Mebendazole as a Repurposed Drug for the Treatment of Brain Cancers. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(2), 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021334

Nath J., Paul R., Ghosh S.K., Paul J., Singha B., Debnath N. Drug repurposing and relabeling for cancer therapy: Emerging benzimidazole antihelminthics with potent anticancer effects. Life Sci. 2020;1:118189. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118189. [PubMed]

Rushworth L.K., Hewit K., Munnings-Tomes S., Somani S., James D., Shanks E., Dufès C., Straube A., Patel R., Leung H.Y. Repurposing screen identifies Mebendazole as a clinical candidate to synergise with docetaxel for prostate cancer treatment. Br. J. Cancer. 2020;122:517–527. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0681-5. [PMC free article]

Sawanyawisuth K., Williamson T., Wongkham S., Riggins G.J. Effect of the antiparasitic drug Menbendaziole on cholangiocarcinoma growth. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health. 2014;45:1264–1270. [PubMed]

Shapiro WR (1971) Studies on the chemotherapy of experimental brain tumors: evaluation of 1-(2-chloroethyl)-3-cyclohexyl-1-nitrosourea, vincristine, and 5-fluorouracil. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 46:359–68. [PubMed]

Simbulan-Rosenthal C.M., Dakshanamurthy S., Gaur A., Chen Y.S., Fang H.B., Abdussamad M., Zhou H., Zapas J., Calvert V., Petricoin E.F., et al. The repurposed anthelmintic Mebendazole in combination with trametinib suppresses refractory NRASQ61K melanoma. Oncotarget. 2017;21:12576–12595. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14990. [PMC free article]

Smart CR et al. (1968) Clinical experience with vincristine (NSC-67574) in tumors of the central nervous system and other malignant diseases. Cancer Chemother. Rep. 52:733–41. PubMed Google Scholar

Son D.S., Lee E.S., Adunyah S.E. The antitumor potentials of benzimidazole anthelmintics as repurposing drugs. Immun. Netw. 2020;20:29. doi: 10.4110/in.2020.20.e29. [PMC free article]

van den Bent MJ et al. (2013) Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long-term follow-up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951. J. Clin. Oncol. 31:344–50. [Article]

Williamson T., Mendes T.B., Joe N., Cerutti J.M., Riggins G.J. Mebendazole inhibits tumor growth and prevents lung metastasis in models of advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2020;27:123–136. doi: 10.1530/ERC-19-0341. [PubMed]

Williamson T., de Abreu M.C., Trembath D.G., Brayton C., Kang B., Mendes T.B., de Assumpção P.P., Cerutti J.M., Riggins G.J. Mebendazole disrupts stromal desmoplasia and tumorigenesis in two models of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2021;6:1326–1338. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.28014. [PMC free article]

Zhang F., Li Y., Zhang H., Huang E., Gao L., Luo W., Wei Q., Fan J., Song D., Liao J., et al. Anthelmintic mebendazole enhances cisplatin’s effect on suppressing cell proliferation and promotes differentiation of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) Oncotarget. 2017;21:12968–12982. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14673. [PMC free article]

* Fenbendazole vs. Mebendazole vs. Albendazole vs. Flubendazole: Because the benzimidazoles are very similar chemically and they have very similar mechanisms of action with respect to disrupting microtubule function, specifically defined as binding to the colchicine-sensitive site of the beta subunit of helminithic (parasite) tubulin thereby disrupting binding of that beta unit with the alpha unit of tubulin which blocks intracellular transport and glucose absorption (Guerini et al., 2019). If someone asks you how fenbendazole kills the cancer cells, the answer is in italics in the previous sentence.

The class of drugs known as benzimidazoles includes fenbendazole, mebendazole, albendazole and flubendazole. Mebendazole is the form that is approved for human use while fenbendazole is approved for veterinary use. The main difference is the cost. Mebendazole is expensive ~$450 per pill, while fenbendazole is inexpensive ~48 cents per 222 mg free powder dose (Williams, 2019). As you may recall, albendazole is the form used to treat intestinal parasites in India and these cost 2 cents per pill. FYI, to demonstrate how Americans get screwed by Big Pharma, two pills of mebendazole cost just $4 in the UK.

While most of the pre-clinical research uses mebendazole, probably because it is the FDA-approved-for-humans form of fenbendazole, virtually all of the self-treating clinical reports involve the use of fenbendazole. It would be helpful if future investigations simply used fenbendazole as a practical matter. For the purposes of this Substack, fenbendazole, mebendazole and albendazole are used interchangably.

Disclaimer:

Statements on this website have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. The contents of this website is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. This website does not provide any kind of health or medical advice of any kind. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. The case reports presented reflect the real-life experiences and opinions of other readers or users of the website. The experiences of those readers or users are personal to those particular readers/users and may not necessarily be representative of all readers/users. We do not claim, and you should not assume, that all other readers/users will have the same experiences. Do you own research, consult with relevant medical professionals before attempting to self-treat for any condition.

The idea with this article was to present some of the peer-reviewed data that is hidden in plain sight regarding fenbendazole and cancer. That scientists studying brain tumors would insist that mebendazole be used instead of the ineffective and dangerous vincristine speaks volumes.

I wonder what this portends?

https://www.kxan.com/news/texas/fda-to-require-prescriptions-for-livestock-antibiotics-aiming-to-stop-drug-resistant-bacteria/

Apparently, repurposed veterinary drugs like ivermectin, maybe FenBen, currently available over the counter, will require a presciption at some point. The FDA is determined to shut down any self help that mihght damage Big Pharma profits.